What is “stigma”? The dictionary definition is:

- a mark of disgrace associated with a particular circumstance, quality, or person: the stigma of having gone to prison will always be with me

This definition gives me pause. Disgraced? To be a person with epilepsy is, too often, to experience stigma. To feel different, somehow lesser. But disgraced?

Well, that definition might explain why my mother behaved as she did when I had a grand mal seizure in the ocean. It was at the beach we had been going to all my life, I was 12, the summer between 6th and 7th grade. I was there by myself, body surfing in the gorgeous Atlantic waves. Luckily, the lifeguards saw me convulsing in the water and dragged me out in time. I came to, vomited up a lot of salt water, felt awful, very tired and was taken home. My mother’s response, after tucking me into my bed, was to tell me I couldn’t wear the same bathing suit (my favorite one!) back to the beach again…it might be recognized…and identify me as that girl.

Or perhaps feeling “disgrace” may explain my friend Violet’s Dad. Upon learning of his 20-year-old daughter’s seizures and the subsequent diagnosis of epilepsy, his reaction was total denial. He blamed Violet, her college girl partying and carrying on. She would not have such episodes if she just cut down on her irresponsible behaviors. Neither Violet, her mother, the doctors, nor any literature on the subject would convince him that his lovely, popular daughter was not at fault. Was it “disgrace” he felt? What my mother felt?

Maybe, but I have a different thought:

Epilepsy is largely Invisible. And unpredictable. Many of us look so “normal.” There is no quickly or easily identified difference (think wheelchair, prosthesis, or another device) that signals our difference. But all of a sudden, with no warning, I may lose consciousness, fall violently to the floor and start convulsing – all limbs jerking wildly. Anyone nearby is taken by surprise, frightened, and often with no idea how to respond or how to help. It is not an easy experience for these onlookers. A co-worker, friend – anyone—can feel betrayed by such an unexpected event, frightened – even if they had foreknowledge of the possibility of epilepsy. It is one thing to be informed and another thing altogether to witness the event. This unpredictable aspect contributes to the stigma surrounding epilepsy.

I’m not saying that “disgrace” is not an ingredient – whether felt by the patient, parent, or associate – but I know there are other elements at work here.

From Wikipedia:

Invisible disabilities, also known as hidden disabilities or non-visible disabilities (NVD), are disabilities that are not immediately apparent and are typically chronic illnesses and conditions that significantly impair normal activities of daily living.

For instance, some people with visual or auditory disabilities who do not wear glasses or hearing aids or use discreet hearing aids may not be obviously disabled. Some people who have vision loss may wear contact lenses. … Those with joint problems or chronic pain may not use mobility aids on some days or at all. Most people with RSI move in a typical and inconspicuous way, and are even encouraged by the medical community to be as active as possible, including playing sports; yet those people can have dramatic limitations in how much they can type, write or how long they can hold a phone or other objects in their hands.

It is estimated that 1 in 10 people live with an invisible disability.

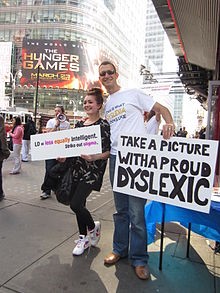

A woman holding a sign that says “LD = Less equally intelligent / Strike out stigma” poses for a photo in Times Square with a man holding a sign that says “Take a picture with a proud dyslexic.” Project Eye-To-Eye to raise awareness of Learning Disabilities Month.

Epilepsy is not the same for everybody. There are many different types of epileptic seizures, each with unique symptoms and each demanding its own treatment plan, thus adding to its mystique and creating fertile ground for subsequent stigma. My childhood beach scenario noted above describes a generalized tonic-clonic seizure, one of the two kinds of seizures that I have and what most people associate with and think of when epilepsy comes up. But this is just one type of epileptic seizure. There are many, and each manifests differently. This great variety of seizures is another ingredient in creating the stinky soup of stigma associated with the disorder.

And this needs to be said: It is all too easy to internalize the experience of this stigma. I get fired from a job, not invited back, and rebuffed one too many times for it not to infect and affect my self-confidence, my belief in myself and my abilities…my potential. And overcoming this is the work that having this disorder tasks us with.

Is it truly disgraceful to have epilepsy? Is the stigmatization deserved? Of course not. In fact, I credit my experience of epilepsy for teaching me to be a creative problem solver, for giving me greater insight and greater ability to persevere through obstacles, and for helping me feel compassion for others — as well as for myself.

These are precious gifts – and far from disgraceful.

November is Epilepsy Awareness Month

OF course not disgraceful. Impressive how you tore down the barriers and made an impact on the world with your gifts and skills. I use to imagine people with hidden challenges could have a sign across their forehead that said youa re talking to a brain injured person etc…and to get a little compassion….but obviously not the answer. We need people to speak up and pout like YOU and treach our crazy world we think should be what we call normal. Am I normal? NO I don’t want to be and rather be ME…and YOU be YOU…lots of appreciation. nina